Stock Record In Shopping Store.One of the most important points connected with the running of any store, is that referring to the manner in which the records of the stock are kept. In most Exchanges, the stock records are not good; usually, because a clumsy or inefficient system of records is in force. An endeavor will be made in the description to be given hereafter to set forth a system whereby misuse of stock will be prevented and an accurate estimate of the profits made by each department will be possible. The objection may be made to this system that in a large exchange it would require the services of one clerk to keep the stock records alone, but when we realize that an inefficient stock record can and usually does result in losses that are sometimes much greater in value than this clerk’s wages, we see the futility of such an argument. It is useless to try to avoid the conclusion that we must keep accurate track of our merchandise. In an exchange at, say, a 5-company post, it is economy to pay one man $100.00 per month or even more, to take exclusive charge of the stock records.

In the first place, it is essential to make clear in the minds of the Exchange authorities the difference between a stock room and a store room. The former is for storing merchandise that is bought in large quantities and will not be needed in the various departments for some time. The merchandise in the stock room is charged to it on the Stock Records until it is needed in one of the departments when it is sent to and its value charged against that department and credited to the stock room. A store room in the sense now considered is a place in which we may store the merchandise belonging to and already charged against any department. This “place” may be but a corner or a shelf in the stock room or any other room. As a general rule, it is best to charge merchandise direct to the proper department, as it saves time and work. Then, if the department concerned finds that it is inconvenient to keep this merchandise on its[51] counters or shelves, it can transfer some of it to the proper store room until needed. Both the stock room and the store rooms should be under the jurisdiction of the stock clerk, the former exclusively so. Efficient locks should be provided for these rooms and he or his agent should be the only persons authorized to handle the stock therein.

The stock record is simply a stock ledger in which we keep accurate account of the numbers of articles acquired and dispensed. If practicable, it should show at all times the exact number of each article that we have on hand. Such a record is sometimes called a “Perpetual Inventory”. It would not be practicable in the usual case for us to keep such a record in post exchange business for the reason that it would be extravagant for us to record each cash or coupon sale made during the day. For example, during certain days of the month, such as pay day and the first day upon which coupons are issued, it is manifestly impracticable for us to make out a sales slip for each cash or coupon purchase because there are so many five and ten cent purchases that the cost in time and labor involved in such a method would outweigh the advantages gained. If the average sale amounted to a dollar or so, it might pay us to use sales slips similar to those used in recording our charge sales. Therefore, most Exchanges do not require cash or coupon sales to be recorded except on the cash register. Hence, there is no itemized record of the merchandise that is sold during the day for cash or for coupons, which in turn makes it impossible to keep a perpetual inventory. The result is that an inventory must be taken at least once a month.

If we now take such an inventory and calculate the selling price of all the goods found, the result will represent the receipts each department should turn in if they sold out all of their stock. If we keep adding to this amount the selling price of all merchandise that we receive for and issue to the departments for sale, and deduct the selling price of all articles which each department turns in to the stock room, we shall have, at the end of the month, figures which represent the receipts which should be turned in if each department were to “sell out”. By subtracting from these amounts the actual receipts turned in during the month, we find the selling price of the articles which should be on hand at the end of the month. By taking an inventory at the end of the month and figuring out the selling value of the articles actually found, we can check the operations of our various departments. If there is any great discrepancy, it would show that our clerks are, in effect, taking articles from our shelves and the Exchange is not getting the benefit of its sales. It is not to be expected that these amounts will agree to the cent.

Now if there is but one clerk in any department, it is easy to fasten the responsibility for any shortage, but where there are several, special steps must be taken in order to do this. Suppose we have four clerks in the store department; if they sell from the various shelves indiscriminately, or if one or more of them are sometimes away on duty, it would be manifestly unjust to hold any particular clerk or even all of them responsible for any shortages which might occur. The only solution lies in sub-dividing the store into sections, putting one clerk in sole charge of each and allow no clerk to touch the stock in another man’s section. In case a clerk in unavoidably absent, an inventory of his section can be made in a few minutes, and, if the results at the end of the month show it to be desirable, checked against the sales he had made. In this way, both the clerk and the Exchange are protected. A “roving” clerk or the Steward can take the place of the absentee in case of necessity. Heavy sellers like tobacco and the like can be placed in the sections of two or more clerks, thus taking care of pay day rushes. Unless some such scheme is adopted it will be absolutely impossible to fix the responsibility for any loss the Exchange may incur.

Those departments which are, in effect, “manufacturing” departments, such as the lunch room, meat market, etc., also require special treatment, especially in the matter of figuring the selling price of merchandise issued to them.

It goes without saying that the honesty of the stock clerk must be above suspicion. In case a civilian is employed, it is good policy—in fact, it should be considered imperative that he be required to execute a bond for the faithful performance of his duties.

With the above general explanation of the broad principles of this particular system, we are now prepared to discuss it more in detail. It seems generally conceded that the stock records can be kept most easily, cheaply and efficiently by means of the card index system. The present regulations, previously cited, specify an “inventory book”, and inspectors are prone to interpret the regulations literally. It makes little difference in our case which method is used, except that the card system is more efficient, as before stated. The handling of the inventory book requires no explanation, so, in order to provide for the time (which should be in the near future) when the up-to-date card system of inventory is specifically allowed in regulations, the following description is given. It is hoped that it will prove a conclusive answer to those who ask, “But suppose you lose a card.”

Inventories of Stock.

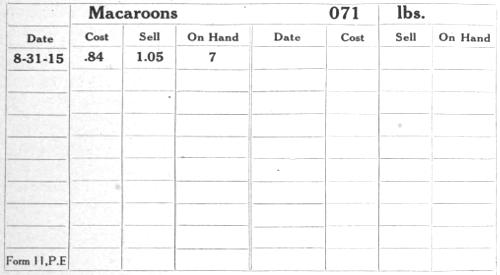

Figure 19, (Reduced in size)

Let us start by taking an inventory of the stock we have on hand in the stock room. We take a pack containing a known number of cards, preferably numbered in sequence, like those shown in Fig. 19, and enter on the top line the name of each article as we come to it; in the right upper corner, the unit in which we sell it, whether pounds, bottles or what not; and at the right of the uppermost data line, the number of such units that we actually find on hand. We do this for each article in succession, using a different card for each. If we have various grades of the same kind of article (cigars, for instance) selling at different prices, a separate card will, of course, be made out for each different grade. (Never sell the same article at two different prices. For example, do not sell cigars for “10 cents each, 3 for a quarter”. Sell them at either price and put in a different brand of equal quality at the other price. It is proper to give reduction on a sale of a box of cigars at a time, but sell them from the stock room in such a case, and not from the store. Another way, permitting sale from the department’s shelves, is by means of a discount slip, which will be touched upon later. The first method, however, probably suits our purposes best, especially when combined with the second.) The cards mentioned above should be left with the articles to which they refer until the inventory for that department is complete. We then look over the shelves to see that there is a card with every article, thereby proving that our inventory is complete, a point of superiority over the book form of inventory. We then gather up and count the cards to make sure that[54] none are missing. The cards are then filed alphabetically behind a tabbed index card referring to that department, or that particular section, if the department is sub-divided. This same procedure is followed in taking inventory of merchandise in the store, lunch room, etc., except that a different colored card is used for each department. All sections of the same department use cards of the same color. As each department will have more or less merchandise in its store room, it will probably be best to take the store room inventories first, then take the articles in the sales rooms. Enter partial totals in pencil and the total in ink or indelible pencil on the first line under the heading, “On Hand”, the date being entered at the left. The number on hand, multiplied by the unit cost and selling prices, respectively, will give the total cost and the total selling price of all the articles on that card. For this purpose, the unit cost and selling prices are entered at the upper left hand corner of each card. The total cost prices are used in our inventories shown on our monthly statement, and the total selling prices are used in our stock records only. In large exchanges, these cards are not used again until the next inventory is taken, so it is seen that they will last for several months.

Merchandise Purchased.

When merchandise arrives, it is cared for as described under “Purchase Records” and when the total cost and selling values of the goods on any invoice have been figured and transportation charges, etc., distributed, the selling values are entered on Form 17, shown in Fig. 20. Two copies of this form are used every day, one for cost prices and one for selling prices. Each invoice requires but one line on each of these forms, so one form is ordinarily ample for a day’s stock transactions. In the left hand column is entered the number of the invoice and in the Dr. column pertaining to each department is entered the selling price of all articles which are covered by that particular invoice. The sum of all the values entered in the Dr. columns on any one line should therefore equal the selling price of all articles covered by the invoice whose number appears at the left.

This same procedure is followed with all invoices received, and therefore covers all merchandise transactions. It will be noted that there are no “Requisitions”, properly so-called, in cases like this where the incoming goods are sent direct to a department. The department head receipts for such goods by simply placing his name or initials in the right hand column of the retained copy of our original order. (See Purchase Records.) This simplified way of handling such a transaction saves an enormous amount of unnecessary work, and is just as sound as the Requisition System.

Transfers Between Departments.

Figure 20, (Reduced in size)

This proposition has previously been mentioned, but we purpose now to show in detail how such a transaction is effected. Let us suppose that the lunch room needs a ham, and it is desired to purchase same from the market department. Assume further that the selling price of this ham is $3.25. It is evident that we must first credit the market with this amount. This is done by means of a “turn-in-card”, Form 12, shown in Fig. 21. The card is filled out as shown, (the name of the article is not essential), is signed by the stock clerk and is given to the head of the market department as a credit for the ham, which is then issued to the lunch room man on a regular requisition. The requisition cards and the turn-in-cards are precisely alike, except that the latter are printed in red ink. With the exception of the signature, therefore, Fig. 21 is also a reproduction of the requisition upon which the ham is issued to the lunch room. These cards are of standard size, 3 × 5 inches, and are[56] of various colors, depending upon the color scheme adopted as described under “Charge Sales”. Hence, we may assume that the market’s turn-in card was printed in red on a buff card and the lunch room’s requisition was printed in black on a salmon colored card. The cards can be bought cheaply with “horizontal ruling”, thus cutting down some of the bill for[57] specially printing the cards. It costs less to have the turn-in cards printed in red than it would to have a special form of card printed, and they are better, besides.

Figure 21

In issuing the ham to the lunch room, the stock clerk should note on the requisition, “Cr. Market”. He then enters the transaction on Form 17 as shown in Fig. 20. In all such transfers, the sum of the credits on any line should, of course, equal the sum of the debits. It is not essential to number these requisitions and turn-in slips because the date stamped at the top is sufficient to enable us to identify any particular transaction. The market man would hand in his credit slip to the Steward with his daily report of sales. The stock clerk would hand in the requisition (receipted by the lunch room man) with his Form 17 for that day.

There is still another transaction for which we must provide and that is the operation of returning to our creditors goods which we have received from them. This may arise through some defect in the merchandise or through some other cause. Such a transaction is handled in exactly the same manner as before. See entry opposite No. 7343 in Fig. 20 where we have credited the store with $7.60. The goods were received on this invoice and deduction made on same for this amount. If this invoice pertains to an account already closed, we can make out an invoice of our own, give it any desired number and give the store credit as before.

Goods which are returned to us by our customers are credited to their accounts through the sales records as before described and do not affect the working of the stock records. Wastage, breakage, etc., is credited to departments by means of this same “turn-in” card; so, also, is discount given on goods sold in quantity, as a box of cigars, for example.

Since the whole operation of accounting for our goods on the basis of selling price is purely for the purpose of protecting our stock, and not for the purpose of calculating our monthly profit and loss sheets, it is seen that it is necessary to make out another copy of Form 17 daily, in order to record the same transfers, issues, etc., on a cost price basis. This will be discussed more fully later, but let it be stated here that this work is necessitated by the rule which requires us to base our statement of assets, insofar as merchandise is concerned, upon the cost price of same. This, for the reason that it is not sound practice to anticipate profits. Therefore, our inventories, when carried as assets, must be based on cost prices, and in order to secure a true statement of profits earned, we must record the cost price of all merchandise that has been purchased during the month and distribute this cost properly among the departments.

At the end of each day’s work, the stock clerk signs his Form 17 for that day and fastens to it all invoices, retained copies of orders (accomplished as previously described) and requisitions that are entered on said Form 17. These papers are really vouchers to this report and should remain with it until they have been checked against it. The whole bunch of papers is handed in to the Steward and Form 17 is checked as soon as possible. After this is completed, the invoices and the retained copies of our original orders which pertain to them are handled as described under Purchase Records; their function as a part of the system of stock records having ceased.

Consolidating Stock Transactions.

The stock record is composed of two parts—one relating to cost prices and the other to selling prices. In all other respects, these two parts are identical and are handled in the same way. Each “selling” Form 17 is entered on a single line of the “selling” stock record, and each “cost” Form 17 is abstracted to a single line of the “cost” stock record. One page of the stock record (Form 27) is shown in Fig. 22. Only the left hand page is shown; the other departments are supposed to be on a right hand page, confronting the one shown in the cut. In cases of departments where credit transfers do not exist, the CR column can be omitted, with a resulting saving in space.

Checking Stock and Sales.

At the end of the month, or whenever our books are closed, we total each column on the adding machine and enter these totals on the next blank line, as shown, and then, when our inventory is taken, the value thereof at selling price is computed and entered just below these totals in the appropriate columns, and subtracted from them. The remainders, it is evident, should equal the total sales for the period considered. In order to compare these amounts, we now enter the total sales for each department in its proper column and find the difference between these figures and those immediately over them, and enter the discrepancies at the foot of the columns. These operations are shown in the figure. Theoretically, the amounts in the CR columns should just balance the discrepancies in the DR columns, but in actual practice, this state of affairs will rarely occur. The resulting net discrepancies, if small, are due, primarily, to wastage, failure to sell exact weights, etc. If these discrepancies are large, the cause thereof should be promptly investigated.

It is easily seen that this scheme permits us to make a check on any[59] department at any time by simply taking an inventory of that department. All other data that we need for such a check are already available, and, as it would not take long to take an inventory of a single department, these checks should afford us a most efficient means of keeping track of our departments. It should be unnecessary to state that these check inventories should be taken without warning, and, preferably, by the Exchange officer himself.

If this system of handling stock is faithfully carried out, one of the greatest chances for “leakage” in the Post Exchange will be absolutely prohibited. It requires work, but no more so than any other efficient stock record, and the results are superior to those obtained from any other system known to the writer. If any exchange employee objects to the system on the ground that it entails too much work, it might be safely assumed that his real objection lies in the system’s efficiency.

Figure 22, (Reduced in size)

PURCHASE RECORDS.

In most Exchanges, the custom obtains of keeping in the ledger a separate account for each creditor, i. e., each person or firm from whom goods are purchased. This entails an enormous amount of work, and as this work can be done by none but an efficient employee, it also entails a considerable unnecessary expense. In the system to be described, this work is reduced to a minimum, and while each of our creditors has his ledger account, this account is kept in such form as to require no duplication of our records, and, at the same time, to tell us at any time exactly how we stand with each of our creditors.

Purchase Orders.

Let us start with the process of ordering our merchandise. This is done on Form 15, shown in Fig. 23. By means of carbon paper, a duplicate of our order is entered on Form 28, shown in Fig. 24. The original goes to our creditor as an order; these orders are numbered consecutively throughout the year, or even over a longer space of time, should it be found desirable. Form 28 goes to the Receiving Clerk and is held by him on a Shannon file until the goods arrive. He then checks the goods against this form and issues them as described under “Stock Records”. A variation of this method, known as the “blind tally”, is worked by making out a triplicate copy on Form 28, this copy to have the “quantity” column blank, which is easily effected by slipping a piece of paper above it to receive the carbon record which would otherwise be printed in that column. The receiving clerk then has no idea of the quantities ordered and fills in the “quantity” column himself. A comparison of this with the duplicate (kept locked up in the office) quickly shows us whether we received all of our goods. This system has broken up some very obscure practices. In either system, it should be noted that we need not await the arrival of the invoice, unless it is desired to do so, before issuing goods to departments. The columns at the right of Form 28 are for convenience in calculating selling prices, etc.

Figure 23

Natural size of sheet about 8 × 10 inches

Figure 24

As previously noted, the receiving clerk (or stock clerk, whoever handles this work) hands in at the close of business each day, two copies of Form 17, one covering the selling price of all stock which has arrived or been transferred during the day, and the other covering the cost price of[63] same. Attached to these forms are all requisitions and receiving records (Form 28) covered by these Forms 17. The Steward sees that each receiving record is correctly calculated and properly entered on both copies of Form 17. (He, also, at this time, sees that the requisitions are properly entered on both forms.) The receiving records are then filed in a Shannon drawer to await the arrival of invoices or for comparison with them if they have already arrived. For convenience, they are filed behind alphabetical guides according to the names of our creditors. When the invoices arrive, they are filed in the same manner and in the same drawer. They would, therefore, naturally tend to find each other.

Before the receiving record is sent from the office to the receiving clerk in the first place, the order is entered in our Purchase Record, which, as its name indicates, is a chronological record of all our purchases of merchandise of whatever sort. Hire of services, of course, is not entered in this record.

Figure 25, (Reduced in size)

There are various forms in use for Purchase Records, invoice Records, etc., and a study of several of them leads us to advocate the use of Form 29, shown in Fig. 25 as being the best suited to the work in hand. This is specially ruled and printed and like most of the other forms described is as well suited to the needs of a small exchange as a large one. They will cost about $12.00 per thousand and a good substantial binder for them will cost from $2.75 to $11.00, depending upon the quality of the binding. One and a quarter inch back is large enough for our purpose; the sheets are 10¼ × 10½ inches, the former being the binding side.

When our order is first made out, we enter in the proper column of the purchase record, the name of the firm on whom the order is drawn. This is the only entry made at this time, and the retained copy of the order (the receiving record) is then sent to the receiving clerk. When the invoices arrive,[65] they are stamped as shown in Fig. 26, the 1st and 2d lines of this stamp are filled in, their date is entered in the left hand columns of the purchase record and the invoices are then filed as before described. In this way, the office keeps track of how fast the stock is arriving, because the number of firm names entered on the purchase record will show us the number of outstanding orders, and the number of dated entries will show us the number of invoices that have arrived which have not yet been checked up by the Steward (usually because the goods have not arrived). When the goods arrive, whether they follow or precede their invoices, and the receiving clerk has checked them into stock and returned Form 28 to the office, the purchase price is entered in the Purchase-Credit column shown. This purchase price disregards our cash discount, which is cared for in the cash book. However, if there is any allowance due us for returning all or a part of the goods on any invoice, the amount of such rebate is entered in the Debit-Purchase column. This is the only use to which this column is put.

Figure 26

Let us suppose that we are now ready to pay a bunch of invoices. Proceed as follows:—

1. Take the invoice file, and, starting with the letter “A”, go through the file, taking the accomplished invoices as you come to them. All those relating to any one firm should be found together, as before mentioned, thus saving much time at this stage.

2. Having your invoices, make out a voucher (Form 14, Fig. 27) for each firm or creditor concerned, entering thereon all invoices relating to that firm. If the buying is done properly, there should be plenty of room on the voucher for these invoices. (In case of a firm from whom we make almost daily purchases, we hold the invoices and make one payment at the end of the month.)

3. As you go along, have a dating stamp handy and stamp the date on each invoice as you make out the corresponding voucher. If the invoice is discounted, stamp the date in the “Discounted” space; if there is no discount, stamp the date opposite the word PAID (see Fig. 26). At the same time, enter the voucher number (which may, and probably will differ from the invoice number) in blue pencil on the proper space of this same stamped impression.

Figure 27, (Reduced in size)

4. When all the invoices are finished, take the vouchers, and, starting with the top one, find where each invoice is entered in the purchase record and stamp the date in the PAID column opposite each entry. These places are easily found by reading the invoice numbers entered on the vouchers.

5. While you are stamping these dates, compare, as you go along, the amount of the invoices as entered on the vouchers, with the amounts entered in the purchase record.

6. Now take the vouchers and enter them in the Cash Book on the right or credit side. In the “net cash” and “creditors” columns should be entered the exact amounts actually paid, in the Discount column should be entered the amount of discount allowed. Discount is always shown in the cash book and on the vouchers in red ink, to avoid confusion with credits, which should be shown in black.

7. After the cash book has been posted, the proper checks are made out, ready for the signature of the Exchange Officer. They and the vouchers are then mailed to the various creditors.

8. The paid invoices are then placed in a Shannon file drawer by themselves where they can be consulted easily. They form a complete file of sub-vouchers to the cash account for the month. They should never be mailed to our creditors for the purpose of having them receipted; it takes too much energy and time to get them back. In case our creditor fails to return our voucher, we can still prove payment, beyond a reasonable doubt, by producing the canceled check (which he must release sooner or later) and the original invoice exactly corresponding to it in value. One authority goes so far as to say,—“If a check bears no evidence as to its purpose but can readily be identified with a particular bill or invoice, it still is a better voucher than a receipted bill, … a mere receipt for so much money, which can readily be forged, is poor evidence of a legitimate payment, but a paid check, properly endorsed and otherwise identified as representing a definite liability, is pretty fair proof that the money has reached the creditors.” (P. 49, Vol. 6, Enc. Commerce and Accounting.)

As a matter of fact, we sometimes experience considerable difficulty in getting even the vouchers back from our creditors. Lieut. Schudt, at the Fort Levett Exchange, hit upon a scheme which tends to lessen this difficulty. This is, simply to have the vouchers printed on a card of suitable weight; the reverse of each card being printed in the form of a self-addressed penalty post card. Our creditor, after dating and receipting the voucher, simply drops it into the mail box without the additional trouble of mailing it in an envelope.

<!–

–>