What Is Sales Charge;Complete Guide You Must Know.This item includes the sale of merchandise to (1) officers, (2) civilians, (3) enlisted men authorized to buy on credit. Such sales are practically cash, being paid, usually, within a very short time.

The practice of extending credit to civilians is not encouraged by the authorities and the Exchange Officer should secure permission beforehand in case it is desired to transact this kind of business. In some cases of isolated posts it is to the best interest of the government that civilians employed or living on the post be allowed credit at the Exchange, as it might otherwise be impossible for the Government to retain their services or for the civilians to subsist themselves. It is to take care of such cases that this feature is mentioned. In opening a charge account with a civilian, care must be exercised to prevent a probability of loss to the Exchange, as one bad account might wipe out the profits from all such accounts for a considerable time. If a civilian is deserving of the privilege[3] of purchasing at the Exchange he should have no objection to conferring with the Post Exchange Officer and making satisfactory arrangements with his employer.

With enlisted men, the case is more difficult. In general, the soldier makes his credit purchases by means of coupons. But if the Exchange handles some such proposition as an ice delivery route, it is impossible to do business with the patrons thereof by means of coupons of the ordinary kind. The right method is to apply to the proper authorities for permission to extend to married soldiers credit to such amounts as may be recommended by their organization commanders. If this is not done, and credit other than in the shape of coupons is allowed enlisted men or if coupons or credit in excess of one-third of the man’s pay be allowed him, the inspector will object to it, as either of these two proceedings is held to be unauthorized. However, when there are no other stores in the vicinity, it seems but reasonable to think that the Post Exchange, instituted purely for the benefit of the enlisted man, should be allowed to extend credit to such married soldiers of good reputation as may be dependent upon it (and the Commissary) for the necessities of life. As the married soldier is usually a non-commissioned officer of long and honorable service (sometimes a first sergeant or non-commissioned staff officer) with one or more children; as the bulk of his pay is usually spent for articles ordinarily carried in stock by the Exchange; as the Exchange is the result of beneficent legislation and the regulations concerning same should therefore be interpreted in a liberal manner, it follows that there is a great deal of justice behind a proper application for permission to make charge sales to such selected men.

In case such permission is obtained, request should be made on the various organization commanders to write a letter of the following purport:—

Fort Jay, N. Y., Mar. 1, 1914.

From C. O., Co. H, 57th Inf.

To Post Exchange Officer.

Subject, Credit to Enlisted Men.

- Request that the following named members of this organization be given credit at the Post Exchange not to exceed the amount set opposite their respective names:

| 1st Sergt. James E. Sullivan | $ 20.00 |

| Sergt. Ralph R. Strouse | 16.00 |

…

(Sgd.) T. R. Jones,

Capt. 57th Inf.

[4]

Method of Making Charge Sales.

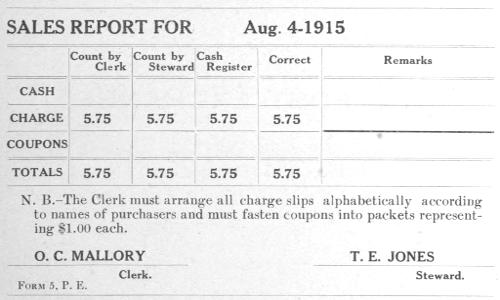

At the time each charge sale is made, the clerk notes the transaction on a “Charge Sales Slip,” provided for the purpose, noting the date, name of customer, name and number of articles sold, the total price of each item, the total amount covered by the slip and the initials of the salesmen. See Fig. 1.

Figure 1, (Reduced in size)

[5]

It has become almost a rule that the purchaser shall receive a copy of this record of sale. Sometimes, he does not receive it until after he has paid his bill at the end of the month, a procedure followed in many clubs and similar organizations. It is probably better in Post Exchange work to furnish the purchaser with a copy of the charge sales slip at the time the purchase is made, as most of our customers wish to keep track of their accounts and also, as will be shown later, this method may be made to promote honesty in salesmen who might be tempted to be otherwise. As it is, of course, essential that we retain at least one copy of this sales slip, it follows that the use of some sort of manifolding device is necessary. There are many such devices on the market, among which may be mentioned as representative, the manifolding sales book and the autographic register. The former is shown in Fig. 2 and the latter in Fig. 3, from which their methods of operation are apparent.

Figure 2.

It is patent that some such scheme should be adopted for use in every Exchange, no matter how small that Exchange may be. The advantages of any of these systems (even a simple duplicating pad) over the painful and inefficient method of recording all such sales in an old fashioned sales record book must be evident to every one. The particular system adopted is of minor importance so long as it is thoroughly adapted to the circumstances of the case involved. The following table is arranged for the purpose of permitting a comparison of two systems; one involving the use of manifolding sales books and the other using an autographic register.

Figure 3.

[6]

| SALES BOOKS vs | CASH REGISTER |

| 1. Can be carried by the salesman, thus saving steps for him. | 1. If a cash register is used the salesman must go to it to record every sale, and therefore if the Manifolder is located at the cash register no unnecessary steps are taken. |

| 2. Cost of 100 duplicating books of simple design with total capacity of 5000 sales is $6.50. Triplicating books more expensive. No first cost for machinery. | 2. Rolls of paper are used; cost of rolls for duplicate records of 5000 sales is from $4.50 up, depending upon the amount of special printing on the rolls. Each machine like Fig. 3 costs, retail, about $15.00. |

| 3. Practically no counter space is necessary for using a sales book. | 3. A convenient place must be left on the counter for use in recording sales. |

| 4. Uniformity in size of slips results in facility in handling and filing. | 4. By exercise of reasonable care the size of the slips approaches uniformity closely enough. |

| 5. The various copies of a slip made from a sales book are more apt to be “in register”—that is, the various lines and spaces of a lower sheet are more apt to be exactly under the corresponding ones of the upper or original sheet. | 5. Sometimes trouble and the expenditure of a sales slip results from the various rolls getting “out of step”. This accident, however, is easy to remedy. |

| 6. The slips can be tampered with, by dishonest salesmen, unless a “slip-printing” cash register, or some special device is used. | 6. By using a machine in which the triplicate roll is wound up inside the machine as it is used, no tampering with the sales records is practicable. |

| (If triplicate records are desired) | |

| 7. We may use either two sheets of carbon paper[1] or only one double-faced carbon sheet below a tissue duplicate and over an opaque triplicate. | 7. We ordinarily use at least two sheets of carbon paper, and all copies are opaque. The machine is adjustable, and will either duplicate or triplicate according to the number of rolls used. It can also be used with a transparent roll. |

| 8. If two carbon sheets are used, both must ordinarily be shifted for recording each successive sale. | 8. The carbon sheets once fixed in the machine require no further attention except when they are worn out or the rolls renewed.[7] |

| 8a. By using a transparent duplicate and a double faced sheet of carbon paper, the latter is the only sheet that requires handling. | 8a. But the slips do not protect us so well because the sales are not recorded on the back of each slip (by reversed impressions) as well as on the front. |

| 8b. In this case, by leaving the transparent slips in the book we can easily check the consecutive numbers of the slips and see that all are accounted for. | 8b. By not tearing off the lowermost sales slip, but leaving it attached to the roll until the end of the day, we obtain a single strip of sales slips recording all the charge sales of the day. They need not be checked for consecutive numbering unless there is a break in the strip. |

| 8c. By previously clipping off the corner of these tissue sheets the book becomes self-indexing and in opening the book we turn automatically to the place for recording the next sale. | 8c. In tearing off the record of each sale we automatically prepare the machine to record the next sale. |

[1]Carbon paper is either single or double faced. By using the latter between two sales slips it is evident that we record our sale on the first and second slips and also secure a reversed copy on the back of the original. It is said that salesmen who alter such slips for their own gain are prone to forget or overlook this point and are caught thereby. No alteration on a sales slip should be tolerated; if the clerk makes a mistake he should be required to cancel and preserve all copies of the erroneous slip and to make out a new one correctly.

It is seen that the advantages and disadvantages of these two systems nearly counterbalance and that the particular system adopted must depend greatly upon the opinions of those in charge of the Exchange. In the following description, the use of triplicating records will be assumed.

In order to facilitate the assorting of the slips handed in by the various “Departments” of the Exchange, it is a good idea to assign distinctive colors to the original charge sales slips of each. (Of course, if there is a very large number of departments, this idea would have to be applied with discretion, as it is hard to recognize certain colors at night by artificial light.) For example, let the original sales slips used in the store be white; those in the market, buff; those in the shoe shop, pink, etc. The duplicate slips should have their own distinctive color and this color should be the same for all departments. If a triplicate slip is used, it should be of still another color and the same for all departments. Following out this scheme, the utility of which will appear presently, a color scheme might be as follows:—

| Department | Colors Assigned to Charge Sales Slips | ||

| Original | Duplicate | Triplicate | |

| Store | White | “Newspaper” | Yellow |

| Market | Buff | ” | ” |

| Lunch | Salmon | ” | ” |

| Tailor | Green | ” | ” |

| Barber | Blue | ” | ” |

| Shoe shop | Pink | ” | ” |

If a system of distinctive colors similar to the above is not adopted, one of two things will be necessary in order that we may identify the slips[8] of each department, unless we wish to do so by wasting the time in deciphering the articles on each slip and decide therefrom the name of the responsible department; we must either have the names of the departments printed on their respective slips when they are made, or these names must be marked on the slips when the sales are made. Neither of these methods is as efficient as that involving the use of various colors, which tells automatically to what department that slip belongs. By using distinctive colors, the printer would set up only one form for printing our whole assortment, and our printing bill would be correspondingly reduced.

In this connection, it might be stated for the benefit of the uninitiated that ordinarily the principal items in our bills for printing, especially in the case of blank forms, will be found to consist of the cost of “composition”, “make-up”, “lock-up”, and “make-ready”. These operations are necessary if but one form is printed; they need cost us no more if 50,000 copies are printed. Paper is comparatively cheap, so it usually costs us little more to print 5,000 copies than to print 1,000. So we can see that in the case of blank forms the cost per unit varies inversely as the quantity ordered at one time. Hence, if we need such forms as sales slips, of which we may use hundreds per day, we should order, say, a year’s supply at a time. Other forms or sheets that are used once a week or once a month must be ordered in lots sufficient to last for a longer time. As we take these up on our Stock Record, such purchases in large quantities will not disturb the worth of the Exchange.

An appreciable amount in the cost of our printing can be saved by a skillful arrangement of the matter on the form. An experienced man can sometimes draft a form so that the charges for printing it will be half what it would cost to print the same form arranged by a thoughtless or inexperienced person. Tabular work costs money, and so also does “special rulings”. Experience or consultation with a practical printer is the only real guide in this matter.

If any form is used in large numbers, it will pay to have electrotypes made, and “repeat orders” printed therefrom. Forms that are seldom used should not be electrotyped, as they will probably require some alteration by the time a new supply is needed. An electrotype costs about $0.25 for the first square inch and about $0.04 for each additional square inch. Here is another opportunity for the exercise of judgment. Suppose we have a large form with printed heading and footing, but nothing in the middle of the sheet; it would be wasteful to electrotype the whole form, only the heading and the footing should be so treated. Now, let us consider the money wasted by having the name of our post printed on each bit of stationery! It is easy to see that this is in some cases a positive disadvantage.[9] Suppose, for example, that Form 8, Fig. 1, fills the requirements of Exchange methods. If a dozen Exchanges order a supply of these forms and (as they usually do) thoughtlessly require that the names of their respective posts be printed on same, they each pay a great deal more than they would if they allowed the printer to make an electrotype of this form and run off all the jobs from the same plate. It is hard, if not impossible, to find any real reason why this extra matter should be placed on many of our forms. Coöperation in matters of this kind would go far toward cutting down some of our “overhead charges” in Post Exchange work, and to secure such coöperation is one of the objects of this paper.

Still another way to minimize our printing bill is to adopt standard sizes for our forms and to use, wherever possible, the same kind and color of paper. Paper comes in sheets of certain sizes and if the printer has to waste a part of each sheet in printing our forms, we shall have to pay for it. Uniformity in size also leads to facility of filing. Incidentally, money may be saved, in some cases by having two or more forms printed together. For example, suppose we have three forms, A, B and C, to be printed on the same stock, and we wish 5,000 A; 10,000 B; and 15,000 C. If ordered separately, these would entail 30,000 impressions. Suppose, however, that they are ordered at the same time, and that the forms are of such sizes (not necessarily equal) that they may be printed together on one sheet and cut apart afterwards. In such a case, a saving might be made as follows:—Set up each form once, make, one electrotype of Form B and two of Form C; place these with the originals and there will result, in one “form” three Forms C, two Forms B, and one Form A, and a “run” of 5,000 impressions will print the lot ordered. There is a saving of the cost of running 5,000 Form B and 10,000 Form C less the cost of electrotypes (if they are not on hand) and of the extra work of locking up and making ready same. Of course, such a procedure assumes that a considerable supply of forms, say, not less than a total of 5,000, is ordered at one time. For a fewer number, there would be no saving unless electrotypes were already on hand.

To return, now, to our sales slips. It will be noted that our triplicate copies are the same for all departments. They are kept in rolls, if manifolding machines are used, or if triplicating sales books are used, the tissue paper sheets that are left in the books form our retained record. In the cases of both the triplicate and the duplicate copies, a cheap grade of paper is allowable on account of the little handling these copies have to withstand. Also, there is no reason for their being susceptible of rapid assorting according to departments. The duplicates are also identical for all departments, they go to the customer at the time of sale. In case there is a discussion about any particular slip, the items thereon will show conclusively[10] to what department it belongs, as will also the initials of the salesman. On the other hand, it is a positive advantage to have all duplicates of a distinctive color, different from that of the originals. Suppose a customer buys a pair of shoes from the store and later returns them. We should then give him a slip crediting him with the shoes at the selling price. To do this, all that is necessary is to fill out a regular charge sales slip in the usual manner except that the word CREDIT is plainly marked on the slip. The clerk then gives the customer the original of this credit voucher and files the newspaper duplicate in the usual way. Upon sorting the slips that night, the duplicate would be noticed, on account of its difference from the other slips handed in and would thus prevent mistakes. Likewise, if it became necessary for, say, the lunch room to buy a ham from the market, the market attendant could make out his charge sales slip as usual, giving the duplicate to the lunch room attendant with the ham. That night, the appearance of this grayish duplicate among the salmon originals handed in by the lunch room attendant would immediately call attention to the transaction. It might be stated here, at the risk of lapsing into the axiomatic, that such a transaction, although favored by some exchanges, is not good business. It should be of rare occurrence and even then needs special treatment. The proper procedure in such cases would be to have the Market turn the ham back to the Stock Room, receive credit for it and then let the Lunch Room draw the ham at the cost price. This point is more fully discussed in connection with Stock Records.

After the attendant has recorded the charge sale in the proper manner and given the duplicate slip to the purchaser, he still has to dispose of another copy (or two other copies if triplicating records are used). The original should be speared onto an ordinary file, each clerk having his own filing hook in a convenient but inconspicuous place. The triplicate is left in the sales book or on the roll, as the case may be. In addition, the clerk should be required to ring up the sale on the cash register. This is, of course, very important, and heroic measures should be adopted to insure the recording of every sale, of whatever kind, on the cash register. Means to this end can readily be devised. The subject of cash registers is a very important one and is discussed in detail elsewhere.

The above operations are described at some length, but in reality, they are simple in the extreme: a customer makes a purchase, the clerk records the sale, rings up the amount on the cash register, gives the customer his goods and a copy of the sales slip and sticks the other copy on his file. If the cash register prints tickets, he may drop the ticket in his compartment of a box or drawer provided for the purpose, or preferably, give it to the customer.

<!–

–>